Speaker 1 (00:00):

We begin all of our programming here with the Pledge of Allegiance, so I ask that you please stand up again and please join me in honoring our flag and all those who serve under it. I pledge allegiance to the flag of the United States of America and to the republic for which it stands, one nation under God, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all. Please be seated. Before we go deeper, I did want to recognize some people who are in the audience with us today. And right up front here we have former Governor of California, Pete Wilson, and his wife Gail. And we have former Ambassador to the Court of St. James Bob Tuttle, and Ronald Reagan Presidential Foundation, trustee Bob Tuttle. Where is Bob? Bob's here. All right. And then of course we have former Congressman Elton Gallogly and his wife Janice.

(01:13)

It's now my honor to introduce Mr. Fred Ryan, the Chairman of the Board of Trustees of the Ronald Reagan Presidential Foundation and Institute. Now, Fred has served President and Mrs. Reagan since 1980 in roles including director of presidential appointments and scheduling in the White House and as President Reagan's first post-presidency chief of staff. In addition to being our board chairman, Fred heads our center on civility and democracy, which supports Ronald Reagan's vision of fostering informed patriotism where Americans can disagree about issues without villainizing each other and where we can find common ground and trust in our democratic institutions. Ladies and gentlemen, please join me in welcoming Fred Ryan. Welcome.

Fred Ryan (02:04):

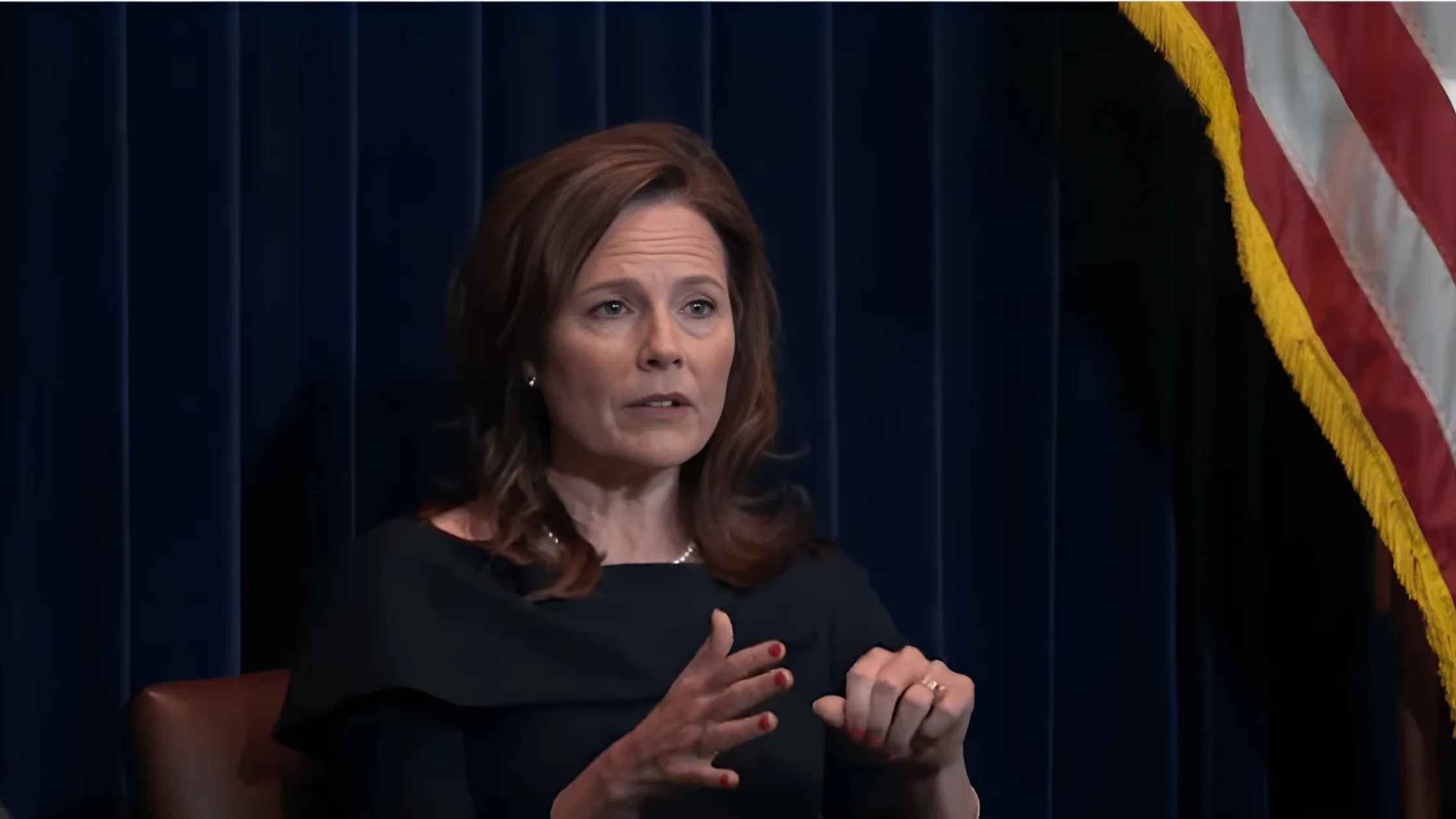

Thank you Dave. Thank you Dave. And good evening everyone. We are honored to welcome Justice Amy Coney Barrett back to the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library. She joined us here last time on April 4th, 2022. And on that visit she talked about maybe writing a book and we said, "When you write that book, would you come back to the Reagan Library?" And proof that she is a woman of her word? She's here with us tonight on the very day her book is released. Thank you. We're delighted that she and her husband Jesse are with us this evening. Supreme court justices hold a special place of honor at the Ronald Reagan Presidential Foundation and Institute. In addition to our special guest this evening, we've been honored to welcome Justices O'Connor, Justice Thomas, Justice Ginsburg, Chief Justice Roberts, Justice Sotomayor, Justice Alito and Justice Gorsuch. And here at the Reagan Library we view Justice Barrett as not just another visitor, but in some ways the continuation of the Reagan legacy.

(03:16)

Earlier in her career, she was law clerk for Judge Larry Silberman, who President Reagan appointed to the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia in 1985. Then she served as Supreme Court clerk for Reagan appointee Antonin Scalia. Now as Supreme Court Justice herself, she brings those experience to her service on the court. Justice Sandra Day O'Connor made history when President Reagan had appointed her to be the first woman on the Supreme Court. Justice Barrett made history of her own as the first mother of school-aged children to serve on the Supreme Court. Now, some have said that being the mother of seven children may be the best possible preparation for the high court. Getting a group of nine to agree on anything is great training. In the introduction of Justice Barrett's book, she mentions a variety of questions that she's received from a wide range of people since joining the court, what was the confirmation process like? What was Justice Scalia like? Did Justices really get along? And from her younger fans, what's your favorite color?

(04:28)

Well, she's organized the book to address three main topics, how she goes about her job, how the constitution shapes our country, and how she interprets the law. As President Reagan said quote, "The country wants and deserves a supreme court that doesn't make the laws, but interprets the laws." And I think he would've loved this book. Just looking at the cover alone, it doesn't say making the law or writing the law, it says listening to the law. And it's a fascinating book. It's very interesting. Having read the book, I would strongly recommend it to two groups of people, those who are lawyers and those who are not lawyers. And maybe there's even a third group lawyers who need a refresher course. In all seriousness, in her words and in her actions, justice Barrett has set an example of what it means to advance civility in our democracy. Her perspective has been a refreshing addition to the court informed and shaped by her years, not only as a jurist, but also as a beloved Notre Dame professor, a parent of seven and a law clerk to two of the most consequential jurists of our time.

(05:40)

Please join me in welcoming Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court, Amy Coney Barrett.

Amy Coney Barrett (05:45):

Am I on this side? Thank you much.

Fred Ryan (06:03):

Well, welcome back Justice Barrett. It's great to have you here.

Amy Coney Barrett (06:06):

Thank you for having me again.

Fred Ryan (06:08):

It's our pleasure. It's hard to believe three years have passed since you were here last, but when you were here last time, you were the new kid on the bench.

Amy Coney Barrett (06:16):

It's so true.

Fred Ryan (06:19):

You've had a few years of experience since then. How has your life changed since then?

Amy Coney Barrett (06:25):

Well, like any job I've gotten more used to it. Justice Scalia used to say that it takes on the court, I can't remember if he said five or seven years before you feel like you really know what you're doing. I wouldn't say that I feel like I really know what I'm doing quite yet, but it's been five years, so I feel like I'm in a groove. I have a system going down, going on in my office, so I'm comfortable now.

Fred Ryan (06:49):

And I know you make a point of asking court clerks what their biggest surprise was. What's been your biggest surprise?

Amy Coney Barrett (06:58):

I always say when I've asked this question, and I still haven't quite gotten over it, the biggest surprise to me was just being a public figure. Justice Scalia was a public figure and he was very much larger than life, but he just wasn't recognized when he went about, and the security needs were not the same, so it's taken me a while to get used to that. But I will say that when I ask clerks that question and say, "What surprises you? What has surprised you now that you've started?" They will often say one of two things, one is, the difference between what's actually happening on the inside and what people think is happening on the inside, there's just such a disconnect. And then that people actually get along here that there's so much communication and friendliness back and forth.

Fred Ryan (07:45):

Well, that's great to hear. And on that subject, I understand there's a tradition that when a new justice is confirmed, the least senior justice holds a themed dinner in their honor. Can you tell us about the dinner you gave for Justice Jackson?

Amy Coney Barrett (08:00):

Yes. As the formerly most junior justice, I got to throw Justice Jackson's welcome dinner. And at the court, the welcome dinner is just for the justices and their spouses and retired justices and their spouses, so it's a very small and intimate thing. And I found out that she really loves Hamilton, so I chose a menu of her favorite food and then found through friends of friends, someone who is a Broadway singer to come and sing for the entertainment some selections from Hamilton, which she liked very much. Justice Kavanaugh did mine and I'm from New Orleans, so we had a New Orleans themed meal complete with Mardi Gras masks and a jazz band playing the Second Line at the end.

Fred Ryan (08:44):

And his theme party was baseball.

Amy Coney Barrett (08:47):

Baseball, he loves the Nats. And so Justice Gorsuch did a baseball theme party with some of the presidential mascots running through the halls of the Supreme Court at the end.

Fred Ryan (09:01):

Well, it's good to know that a party is waiting for you at the end of the confirmation process, but having been through the confirmation experience yourself and then having watched another justice go through it, is there anything that you think should change about the confirmation process?

Amy Coney Barrett (09:18):

The Senate runs the confirmation process, and I certainly wouldn't tell another branch of government how they should conduct their affairs. I think though as a country, when I look at the confirmation process, Fred, you were talking before about civility, I think the confirmation process, if I could change something, it might be less about the process itself, but just about how we as Americans react to it because I think that the confirmation process is often characterized by a lot of incivility. And I'm talking about in the national conversation, not in the hearing room itself.

Fred Ryan (09:55):

Got you. Now, sometimes things we say early in our lives can come back to haunt us. And I came across a quote by you back from your days when you were a law clerk at the Supreme Court and it was about the Supreme Court cafeteria. And you said quote, "It was not a place you would choose for a date night." That's not a very nice Yelp review, but has it changed at all?

Amy Coney Barrett (10:23):

The cafeteria, it's the job of the most junior justice to supervise the cafeteria. And I don't have to do that anymore, now it's Justice Jackson, but traditionally a justice will choose some food that the justice would like to see in the cafeteria. And I really wanted to have Starbucks in the cafeteria. We do. It's We Proudly Serve. It's not the actual franchise. The cafeteria has been spruced up. There was a renovation that happened right after COVID, so it looks a lot better. And now that I have supervised the cafeteria for a while, I would say you should take a date there.

Fred Ryan (11:07):

Let's get into the book. And one of the purposes behind your doing the book was to demystify the processes of the Supreme Court. And could you take us behind the scenes, if you could, from what happens from the time somebody petitions the court for a hearing to the hearing, to the briefs, the arguments, the deliberation, and then the rendering of the decision?

Amy Coney Barrett (11:31):

Yes. I think when people find out about the court's work, it's usually at the very end of the process. It's usually when you see the headline saying, this is what the court decided. But really the case would've started at the court anyway, months and months before that. We get about 4,000 of what are called petitions for certiorari every year. And those are requests that the court take a case and we wind up taking only about 60 cases a year on the merits docket, so the chances of anyone petitioned for a certiorari getting granted are pretty low. And that's because the court really, referee isn't quite the word that I want to use here, but the court resolves conflicts that exist among other courts throughout the country. When other courts, courts of appeals, state supreme courts, disagree about a legal issue the Supreme Court steps in and resolves the issue to get it right. But otherwise, we let the lower courts stand. We don't take cases just because lower courts, we think they might've gotten it wrong because they're out there, federal district courts and circuit courts deciding cases, and we do not interfere.

(12:46)

We get involved when there's a reason of national importance, the need for a nationally uniform rule, because there are disagreements around the country. We take a case and then we set it for argument. We read a lot, a lot of briefs, we hear argument, then the justices meet to decide the case. When we meet in the conference room, it's only the nine of us. There are no assistants, there are no law clerks, so we have to do all of our own work and the door is shut. And one thing we were talking about jobs of the most junior justice, the door is shut, it's only the nine of us inside that room. And if anyone needs to come in that room and they knock on the door, the most junior justice has the job of answering the door, so the junior justice has to leap up and stand and make sure that it's someone who has business there and hand the sweater or the briefs that we're forgotten or pass the message along as the case may be.

(13:47)

Then we discuss the cases in the room, and this is after we've already had the case on the docket for quite a while and there've been other steps of the decision-making process, so I don't know if you want to-

Fred Ryan (00:00):

Fred Ryan (14:00):

Well, I'd like to just go a little bit more on that because one thing you mentioned in the book, you talk about seniority within the court and when the deliberation and decision-making discussion takes place, it's based on seniority. The most senior justices speak first and then eventually the more junior justices speak. And I know you mentioned that sometimes it's possible that they've made up their mind before the junior justices even get to speak. Could you tell us how that process works?

Amy Coney Barrett (14:27):

Sure. So we do a lot of things at the court in order of seniority. As you can tell, just from my saying that the junior justice runs the cafeteria that answers the door. So the way that we speak at conferences, it goes in order of seniority with the chief justice, who's always the most senior person speaking first. So I speak eighth and Justice Jackson speaks ninth. And so people will go around the table and express their views about the case. And so by the time it gets down to me, many other people have already said what they think about the case. Justice Stevens used to say that when he was the most junior justice, he found that very frustrating and he advocated for a change of order so that the junior justices could sometimes go first and have an opportunity to set the tone of the discussion. I can see advantages and disadvantages both ways.

(15:20)

On the one hand, if you're at the end of the line, you can shape your comments to address the issues that you know people actually care about. Because when you're speaking at the beginning, you're not really sure exactly what the big points of disagreement are going to be.

(15:34)

The flip side is you lose a little bit of your power to persuade, but people do come back around. I mean, people might say, "Oh, well, what Amy said, I find that really interesting and I want to add this point." So it's not that you have no opportunity to shape the conversation whatsoever, just because you go at the end.

Fred Ryan (15:54):

Maybe it could be alphabetical, you and Justice Alito would probably like that.

Amy Coney Barrett (15:57):

Ah, that's true.

Fred Ryan (16:02):

One thing that's in the news a lot that people have been talking about is the court's emergency docket. It's getting a lot of attention, and I suspect most people who petition the Supreme Court feel that that case is very urgent and it requires immediate attention. So how does the court look at all the cases that come in and decide which one should be under the emergency docket and which should be under the normal process?

Amy Coney Barrett (16:25):

I'm so glad you asked that because that is question that people have been asking a lot because the emergency docket has been in the news. So when I was describing all these petitions for certiorari that come in, you can think of it as two tracks. All those petitions for certiorari are what's on, we can think of as, let's call it the merits docket, and that's the regular docket. That's what we've always decided. That's kind of the slow moving process. These cases that come on the emergency docket, it's a different track altogether. And on that emergency docket, these are cases that are still pending in the lower courts. So they're not coming to us for final resolution. It's not an appeal from a decision that the lower court has made such that we're taking it and we're resolving it finally.

(17:13)

When cases come in the emergency docket, they're cases that are asking for what's called interim relief and they're saying, listen, let's imagine a lower court entered an injunction. They're saying this is an emergency, we need quick action because while this case is being litigated, I mean, let's say that some policy of the administration has been enjoined. The administration might say, "While we are litigating this case, having this injunction in place is harming us, is irreparably harming us in a way that we can't cover from. So in this interim, please stay this injunction while we're litigating the case."

(17:56)

So it's really about what is the status quo going to be while the litigation happens? And the court, when we weigh in on that, we're not definitively resolving the question. We're asking a series of questions like, "Well, if you're going to ask us to say this injunction, you have to show us that it's more likely than not that you would win in the end, that it really would cause irreparable harm if we don't stay this injunction while things are playing out." But I guess the big thing I would say is these are not final resolutions. These are kind of quick things that are happening in the interim while these cases are still being fully litigated below.

Fred Ryan (18:34):

I see. Another thing we talked about when you were here last was the question of whether cameras should be in the Supreme Court, and you said that if cameras were added, it could change the nature of the proceedings. Has your view changed at all on that

Amy Coney Barrett (18:49):

It has gotten firmer.

Fred Ryan (18:50):

Okay.

Amy Coney Barrett (18:52):

Yeah. I think that the court, we often imagine that if cameras were visible someplace or present someplace that there would be like a fly on the wall recording it. I don't know. The court moves slowly, change comes slowly, so cameras would be a really big change. Right now we're streaming audio and that might not sound like a big deal, but that didn't start happening until COVID. So we do livestream the audio, we just don't have the cameras and the video. But I mean, again, I'm one person of nine. It's not my call. It's an institutional decision by the court, but I think the audio is good for now.

Fred Ryan (19:27):

Got you. One thing, people who have toured the Supreme Court are always fascinated about is the basketball court above the court chamber known as the Highest Court in the Land. Have you had a chance to use that? And I wonder, is that a place where seniority is not an advantage?

Amy Coney Barrett (19:45):

I think seniority probably is not an advantage there. That's true. The law clerks do play a lot of basketball up there. I will confess that I have not joined the law clerk basketball game, so I have gone up to the Highest Court in the Land. My kids have gone up and shot some hoops in the Highest Court in the Land, but I have not myself joined the fun.

Fred Ryan (20:05):

And your clerks play against other justices' clerks or is that …

Amy Coney Barrett (20:09):

Yes. So the clerks have running games where all the law clerks, each justice has four law clerks. The law clerks will all go together and they play basketball games and they've kind of got running intramurals going on.

Fred Ryan (20:22):

Fantastic. In terms of the path to become a Supreme Court justice, you're the only current justice who did not receive a lot of degree from Harvard or Yale, with close to 200 law schools, there are something like 200 law schools in the United States. What do you think about such a heavy concentration of just two schools?

Amy Coney Barrett (20:48):

I think people choose schools for all kinds of reasons. So I think that we shouldn't … I don't think we should weed out, I had two law clerks from Harvard last term who were fantastic, but I also had two law clerks who were from Notre Dame Law School last term, and they were fantastic. So I don't personally, when I'm choosing law clerks, only limit myself to only those two schools or any other small pool of schools. So no, I don't think any two law schools should corner the market on that and go Irish.

Fred Ryan (21:23):

Well, on that subject of sports, and I asked this of a Notre Dame alum very cautiously because you are in the center of USC Trojan territory here, but you once said you could teach the other justices "A thing or two about football." Have you been successful?

Amy Coney Barrett (21:46):

For some maybe, but I have some colleagues who have become very avid Irish fans. And I will say that I might be deep in your territory right now, but you'll be in our territory in October.

Fred Ryan (21:59):

Your territory has been pretty rough lately.

Amy Coney Barrett (22:01):

It's only one game.

Fred Ryan (22:06):

A lot of people think that in order to be on the Supreme Court that you have to either be a judge or at least be a lawyer. But being a lawyer is not a prerequisite for the Supreme Court. Do you feel that it should be, or do you think there is another life experience or a career path that would be helpful as a justice?

Amy Coney Barrett (22:23):

It's so true. It's not in the Constitution that you have to be a lawyer to be a judge of any kind, much less as Supreme Court Justice. I think it would be pretty tough if you weren't a lawyer. So I mean, I wouldn't advise someone who wasn't a lawyer to give it a go. But at the time of the founding, and for many, many, many, many years after that, justices, lawyers were not trained formally in law schools. So in fact, Justice Robert Jackson, who was an FDR appointee, I believe he was the last justice who did not have a law degree. He was a lawyer, he'd been a practicing lawyer, but he hadn't gone to law school. He had apprenticed. So that's not the system anymore. And I think it probably is good though we know something about the law.

Fred Ryan (23:13):

Speaking of judges, what's your view on term limits for federal judges? I know sometimes younger judges are in favor of them, but when they get older, they oppose them.

Amy Coney Barrett (23:26):

So Jesse, my husband, when I became a judge and I was on the 7th Circuit, he told me, just kind of looking at the future and what our life might hold, and he said that he would get extremely offended at some point if I did not retire, because it would be a sign that I didn't want to spend time with him. So I think at this point, the Constitution has been understood to give judges life tenure during good behavior and salary protection. So term limits would require a constitutional amendment it seems for federal judges. There seems to be agreement on that.

Fred Ryan (24:02):

Talking about the Constitution, you've devoted a lot of your book to that. Most countries have a constitution in one form or another. And one thing we were talking about earlier, President Reagan, before he would meet with a leader of another country, he would frequently read the Constitution of that country just to have a better understanding, better perspective. But in the book, you talk about the importance of our written constitution as a supreme law of the land, and why is America so consistently held to those original written words for over 200 years, while other countries have changed or updated their constitution so often?

Amy Coney Barrett (24:39):

It's really incredible. We had the first written constitution in the world, and we now have the oldest written constitution in the world. And Americans have really stuck with our Constitution for all these years. And I think that its longevity is attributable to a few different things. One is its brevity. It's pretty short. You can have a pocket constitution. One story that I tell in the book is that Senator Robert Byrd was famous for always carrying a pocket constitution with him. And then towards the end of his life when he was older, he would be rolling in a wheelchair through the capitol, holding the Constitution out in front of him, saying, "Make way for liberty." It's small enough that you can put it in your pocket.

(25:23)

If you look at some of the constitutions of other countries, they're very, very long. They're very, very thick. They couldn't be a pocket constitution. And the fact that it's a pocket constitution, it leaves us room to regulate most things through statutes and through regulations and those things that are easier to change, things that can more easily evolve over time. So we really kind of keep it to the basics in our Constitution. And then we put most things into the democratic process of contemporary politics.

Fred Ryan (25:54):

And you talk a lot about just the unique nature of the written constitution and the advantages of that. Could you talk a little about that?

Amy Coney Barrett (26:01):

Yeah. So our English forebears, the founders and the drafters of the Constitution knew well their rights as Englishmen and were very familiar with English law, which did not have, and England still does not, the UK does not have a written constitution. It's kind of made up of traditions of the Magna Carta, some statutes. It's kind of an amalgam of different sources of law, but a written constitution is pinned down. Unwritten constitutions change, they can evolve over time and they can change without people really knowing it because change can be gradual. We have to amend our Constitution to actually see that change. And I think having it committed to writing does a few things. It puts us all on the same page. I mean, we all know that we have freedom of speech, and we might disagree about how that freedom applies in any particular circumstance, but we would all in the room agree that the Constitution protects our freedom of speech.

(27:06)

If that weren't written, we might have disagreements about the antecedent question of should we protect free speech? Because if you were going to go back to the drawing board on that, there might be people who would say, "Well, there are reasons to not really protect free speech as much as our Constitution does, and so maybe we shouldn't commit that to writing." So I think committing things to writing hardens them. It makes it harder to escape those obligations. It makes it harder to have disputes. It makes it impossible to have disputes about whether rights exist. We just focus on how those rights apply. But we all know that the rights exist.

Fred Ryan (27:45):

And on the subject of the Constitution, you quote President Lincoln as being correct when he described the Constitution as part of the "Political religion of the nation." Why do you think that's a good description of America's relationship with the Constitution?

Amy Coney Barrett (00:00):

Amy Coney Barrett (28:00):

Because it's what unites us as Americans. Some countries may have a religion in common because there's an official established church, like the Anglican Church. Right? We don't have that in America and we never have. We are of many, many different religions and of no religion at all. We come from vastly different backgrounds. Our country is huge. When you compare the expanse, the size of the population and the landmass of America compared to say other Western European countries, we're huge. But we are united despite our differences by the fundamental commitments that we have made in our founding document. And so Abraham Lincoln was saying, this is something that we hold in common. This is what we are committed to as Americans, and it's what defines America.

Fred Ryan (28:55):

Last time you were here, you talked about the importance of civility and collegiality. Even saying that you thought that those were important principles that future lawyers should learn, and I love this quote in your book, you said, "The success of a multi-member Court rides on the ability to disagree respectfully. The success of a democratic society does too." Could you talk a little bit about why civility is essential to the success of our democratic society?

Amy Coney Barrett (29:21):

Because a democracy requires compromise. We can't govern ourselves if we're not willing to compromise and meet in the middle. Moreover, we're all in this together. And if we have a winner-takes-all approach where you just want to crush the enemy, if you regard people who disagree with you as the enemy, we can't constructively move forward as a society. I mean, when you look at what the founders accomplished in reaching agreement about the Constitution itself, even those who drafted it at the Constitutional Convention, Ben Franklin left and he said he wasn't fully satisfied with the document, but he couldn't imagine… It was a miracle that they had come up with as much agreement as they had. And we still have that same Constitution today. I just don't see how we can live together in our common project of building America unless we're willing to see one another as fellow Americans, compromise, and move forward.

Fred Ryan (30:29):

At the Reagan Center on Civility and Democracy, we think a lot about how Americans can disagree better. In fact, we have a program called the Common Ground Forum. And in the book, you talk about how Justices Scalia and Justice Ginsburg who didn't share a lot of the same views, found common ground. Could you tell us about that?

Amy Coney Barrett (30:49):

Sure. They were very, very close friends. They would have New Year's Eve dinners together. They went to the opera together. There's a picture that I have in the book that's a famous picture of them in India together riding an elephant, but they disagreed heatedly so on the page in opinions. So as Fred says, jurisprudentially, they had a lot of differences. He took a more conservative originalist approach to the Constitution, and I would describe her approach as more of the progressive living constitutionalist approach. He was a Republican appointee, she was a Democratic appointee.

(31:27)

But despite those differences and different ideas, they had about very important things, personally, they got along very well. They could be warm. And I think that's a good example for us about what we should strive for in our relationships. You don't have to destroy enemies and you don't have enemies about ideas. Justice Scalia used to say, "I attack ideas, not people." I think that's how we should think about things. You might disagree with someone's ideas, but that doesn't mean that you dislike or want to destroy the person.

Fred Ryan (32:04):

It's been well-known over the years that President Reagan, who had Tip O'Neill as Speaker of the House. Ronald Reagan being a conservative Republican from the west, and Tip O'Neill being a liberal Democrat from the east, they didn't share a lot of similar political views, but they managed to get things done and they would get together at the end of the day and sometimes have a drink and tell Irish stories. Well, there was a story in your book that reminds me of President Reagan's approach. Could you tell us about Chief Justice Marshall and Justice Story and how they were bonding over wine and the weather?

Amy Coney Barrett (32:38):

Yes. So Chief Justice John Marshall is known as the Great Chief Justice. He was a John Adams appointee, but he's really the one that solidified the power of the Court and made it a co-equal third branch of government. And one thing that he did was he really brought the justices together. At the time, the justices did not live all in the capital city and they lived… Marshall himself lived in Virginia, some lived in South Carolina, and they would only come together when they heard cases and they would stay in scattered boarding houses around the city.

(33:14)

And so he instituted a practice of having them all stay together at the same boarding house so they could become friends. And they would eat meals together and they would discuss cases over the meals. And Marshall really loved a good Madeira, and story was a little bit more buttoned up, and Marshall said, well, we can have it when it's raining. And then when it was sunshiney, story would say like, well, I don't know what about the weather? So Marshall would look out the window and say, "Our jurisdiction is so vast. I'm sure it is raining somewhere within our great jurisdiction." And they would have the wine anyway. And I think that food and wine and time together are what enable people to form friendships and work collaboratively.

Fred Ryan (34:01):

And talking about Chief Justice Marshall, one thing you mentioned in the book is a tradition he began of the robes. And before that time, justices would wear robes of any color or any design they wanted. Some wear their school colors. Could you talk a little bit how he moved it to the black robe and what that stood for?

Amy Coney Barrett (34:18):

I love this story. I was reading a biography of John Marshall many, many years ago and read this story. So John Jay, who was the first Chief Justice, was sworn in, and when you see portraits of him, you can see him in brightly colored robes. And that was the English tradition. And so that was what judges did in the early years of the country. But when John Marshall came in, when he was sworn in, he decided to wear just a plain black robe. And his idea was that he wanted to show that this was a humble branch. It was a sign of humility and modesty.

(34:50)

And when all judges in the years since have mimicked that and all started wearing black robes, I think it's also just taken on, it shows that we're not there in our individual capacities. We're not using robes that make a statement or show something about our own background because in the old days, those colored robes sometimes were the robes of the university that the judge had attended. I mean, I guess I would kind of like a blue and gold robe perhaps. But it shows that we are there. We're not partisan, we're there in an impersonal way. We're all dressed alike, we're dressed modestly and humility, and we're there to interpret the law.

Fred Ryan (35:33):

Looking forward into this next term, the Court will issue some opinions and some very high profile cases, one on tariffs who just announced today. And without getting into the individual cases, but regardless of how they're decided, some of these cases will leave a segment of Americans disappointed and possibly angry. At a time when the Court is under so much scrutiny, how does the Court preserve the dignity and the respect that it needs to fulfill its constitutional role?

Amy Coney Barrett (36:01):

I think that the best thing that the Court can do is what the Court has always tried to do, and it's to not decide cases with an eye towards political reaction, popular reaction. I think that when the Court tries to… If the Court were to try to decide cases in a way that it thought the public wanted it to, it would be doing its job because sometimes what the law requires runs counter to what the majority may want. And I think the way that the Court can conduct itself is to try to assure the American people that what the Court is really doing is law and not politics. And one thing that I always encourage, and I'm not alone, many justices over time… Justice Sotomayer was just saying this in a public appearance today or yesterday, "Read the opinions." I try to say this in the book, read the Court's opinions and not just headlines or snippets about the opinions because that's where you can try to hold us accountable. And that's where you can see, that's where we try to show our work.

(37:06)

And for us to have your trust and for us to show institutional integrity, our opinions have to hold up. Their logic and their analysis has to hold up. And you might disagree with them when you read them, and that's great. I mean, well, not if it's one that I wrote, but then we can have a debate not just about the outcome, but about the logic of the opinion. And as long as the Court is sticking to an honest effort to do law and to show its work, I think we can do no more to try to discharge our institutional responsibility.

Fred Ryan (37:40):

But we're in an era where there's such distrust of institutions and decline in public reviews, and the Court has not been immune from that. Public perception of the Court's declined in recent years. Do you have a thought why that is?

Amy Coney Barrett (37:55):

I feel like we've lost… Or, Americans have generally lost faith in institutions. And I think we're coming up on America's 250th birthday, and I think… I hope that Americans use this occasion of this anniversary to have faith in America. And if we're going to have faith in our country, we need to have faith in the institutions of the country, not just the Court, but all of our country's institutions, all of our institutions of government. And I think that institutions can only flourish. Our institutions of government can only flourish when Americans have faith in them, but I think that takes engagement. That's one of the things that I was hoping to do in the book, is by inviting Americans to see how the Court functions, to invite Americans to invest in the Court and to feel like they have a stake in the Court, which is something that belongs to all Americans.

Fred Ryan (38:53):

You talked a little earlier about some of the specific things in the Constitution and then some of the general things. The specific thing being, for example, in order to be President of the United States, you have to be 35 years old, and that's something people can pretty much agree on. But then there are the general areas that require interpretation. And I was just wondering more from your years as a law professor, have you ever wondered how people could differ so greatly when it comes to the interpretation of those general terms?

Amy Coney Barrett (39:22):

So not really because people disagree so much about so many things. I mean, one thing that is remarkable is how much agreement there actually is about many things. The Court, when you look at our docket overall, we hover at just below 50%, maybe around 45% of unanimity every term. So that's a lot of cases where we're all unanimous. But one of the things about the Constitution's general language, like the protection against unreasonable searches and seizures, when you have a word like that, unreasonable, there'll be a range where everybody will say, outside of this, we all agree this is unreasonable. Then there's a range right here where we all say this is reasonable, but then there's going to be a band where there's room for disagreement. One of the great things about the Constitution is that it leaves some of that play in the joints.

Fred Ryan (40:22):

When we spoke earlier, you talked a little bit about Justice Scalia, who you clerked for, and he was known for mixing strong convictions with a great sense of humor. What role does humor play among the justices today? And is laughter something, a tool at the Court for civility?

Amy Coney Barrett (40:41):

I think laughter can be a tool for anyone for civility. I think it's a great way of breaking tension. I have a friend who clerked with me the same… Who clerked at the court the same year that I did, who used to track, I'm not sure if he's still doing it, the number of laughs at oral arguments that various justices would elicit from the bench when they cracked jokes during argument and can bring a little levity to the courtroom. Lunches, we have lunch together after argument and after conference, so we lunch together frequently and regularly. And a lunch would be pretty boring if it didn't include some laughter. So yeah, laughter and jokes are part of relationships.

Fred Ryan (41:25):

One thing that I know Supreme Court justices get to do, even if the most junior justices, you get to determine the artwork in your offices.

Amy Coney Barrett (41:32):

True.

Fred Ryan (41:33):

And you chose to hang a portrait of Abigail Adams. What made you choose her?

Amy Coney Barrett (41:38):

So the Constitution involved a lot of history on a lot of my job as reflecting on the founding era and what did these provisions of the Constitution mean at the time they were adopted. And I wanted to have something in my office that was representative of that founding era. And I admire Abigail Adams. I've read her letters to John,

Amy Coney Barrett (42:00):

And I've read biographies of her various papers, and she's kind of the closest thing that I think we have to a founding mother. She was so engaged in everything that was happening at the time of the founding. She was offering John advice. Obviously, women couldn't participate in either the constitutional convention or the ratification, the state ratifying conventions. But she was very involved, and she's just kind of that symbol to me of women at the founding era who would have wanted to be able to do the job that I have now, but we're unable to then. We've amended the Constitution, so now the franchise is expanded, and our political participation is expanded out far beyond what it was at the time of the founding. And Abigail was also, she was a mother. She raised a large family while John was away doing all of the affairs of the country. She was home managing the home front. So I think she had her foot in two worlds just as I do too.

Fred Ryan (43:04):

And speaking of the work he was doing at the Constitutional convention, it seems, looking back, people have written that amazing steps were taken to assure the privacy of those conversations there, that the doors were locked, the shades were drawn, so outsiders couldn't see or hear the debates. And some have wondered if, without those steps, whether they could have achieved the outcome that they did. What do you think about that?

Amy Coney Barrett (43:27):

Even if there were cameras at the Constitutional convention?

Fred Ryan (43:30):

They banned cameras. I understand.

Amy Coney Barrett (43:33):

I think there's something to be said for that, right? I think that sometimes compromise maybe is best reached behind closed doors. I don't know what a member of Congress might say about that now, whether compromise would be easier reached if it was done constitutional convention style for some of it. It would be in the room where it happened.

Fred Ryan (43:57):

Right.

Amy Coney Barrett (43:58):

I think at the time that the Constitutional convention was meeting, when they went, they were initially supposed to just be amending the articles of Confederation, and they wound up throwing the articles of Confederation out and starting an entirely new project. And if people had been aware of that from the very beginning, the project may not have gotten off the ground. So I think it probably did really make it possible.

Fred Ryan (44:25):

In introducing you, I mentioned two Reagan judicial appointees that you clerked for Justice Scalia and Judge Silberman. In some ways, they were mentors. Could you talk a little bit about how they shaped your view on civility, but also prepared you to be a justice?

Amy Coney Barrett (44:40):

Yes. So they were both brilliant. They were both fun, funny, they both invested in their law clerks, mentored me for the years, many years after the clerkship, took a personal interest in me. Justice Scalia had passed away, obviously, by the time I went on the Court, Judge Silberman was still alive. He swore me into the Seventh Circuit, and he was in the Rose Garden when my nomination to the Supreme Court was announced. He was with me in the hearing room for the Seventh Circuit for the Supreme Court. The hearings were closed because of COVID. So they both played big parts in my life, not just as intellectual examples and intellectual mentors, but also as personal mentors. And so, I think I've taken away from them not only my approach to the law, I've also modeled the way I run my chambers and the way that I relate to my law clerks and the importance that I put on relationships.

(45:37)

At Judge Silberman's funeral. He passed away a few years ago. On the civility point, Judge Silberman, as Fred said, was a Reagan appointee. Merrick Garland was a dear friend of his, and he was Attorney General, obviously, in the Biden Administration. And he had been a democratic appointee to the DC Circuit. So they had been judges together. They had served on the DC Circuit. He gave one of the most beautiful tributes at the memorial service. Judge Silberman was friends. He worked hard on collegiality on the DC Circuit. And it was just such a moving experience to hear people with whom he had disagreements, that were jurisprudential or political or whatever, coming together to honor their friendship because that had been really important to him.

Fred Ryan (46:28):

And speaking of Justice Scalia, and I am paraphrasing this, but you mentioned something in the book about how he said good jurists are not always happy with the results of their decisions.

Amy Coney Barrett (46:40):

Yes.

Fred Ryan (46:41):

Because that means they've had to put aside their own political views, their own moral views. Could you talk just a little bit about how that works?

Amy Coney Barrett (46:47):

Yeah. He said if you're always happy with the results you reach, you're not doing something right. Because it's inevitable that you will be unhappy with the results that you reach. Because, if you're kind of following the law where it leads, it's going to sometimes take you places where you would just as soon not go. So I take that he was very rigorous about putting aside personal convictions and saying that the law was about process. You're following the law, and you're listening to the law, following it where it takes you. So what I try to do is, when I'm deciding a case, and let's say it's a question of Congress's authority to do X, and I don't really like X, to try to make sure that I'm not biased on the constitutional question because of the particulars of the policy, I will imagine Congress having done Y, something I do like. And what do I think about the constitutional question then? It's kind of a way of checking myself to make sure I'm keeping myself honest.

Fred Ryan (47:57):

There are a lot of lawyers and some future lawyers who are here with us this evening. And what would you like them to take away from your service on the Supreme Court, and how would you like your work to be an inspiration to other young Americans?

Amy Coney Barrett (48:12):

Well, I want Americans, young Americans especially to take pride in America, to take pride in the Constitution, to have faith in the institution of the Court. And I think for lawyers, I think the craft matters, the work matters, the law matters. Some people might be cynical and say, "Oh, it's not really about law. It's all politics." And that's not true. And when you look at the body of the Court's work over time, you see it is about the law and people have disagreements about the law and the Court makes mistakes. The Court has made some big mistakes over time. So I'm not saying that the Court always gets it right, it's a human institution, but it is about law, and it is about justices trying to get it right. And so, as young lawyers, as future lawyers, I hope you invest in that and believe in law.

Fred Ryan (49:06):

Now for young lawyers and for other lawyers, technology has changed the legal profession a bit already. Some of the things that used to have to be done: shepardizing cases and going through tons of volumes is now done with a few keystrokes on the computer. A question that came up earlier is with technology changing things, what about artificial intelligence? Does that have any formal role at the Court now? Do you see it in the future?

Amy Coney Barrett (49:34):

So artificial intelligence doesn't have any formal role at the Court now. We don't use it in working on opinions. We don't use it for research. And I don't think we would for the foreseeable future because just of confidentiality concerns. Once you have things out in large language models, then it's no longer confidential. But I am sure that just as AI is changing every other aspect of our life quite rapidly, at some point it will have some effect. It's just that the Court moves slowly because the Court…

(50:10)

When I was a law clerk, the internet was invented. I'm not quite that old, but we weren't allowed to work remotely because we weren't allowed to have any kind of line in or check our email from the Court. So you had to do all of your work physically in the Court and you couldn't email from inside the Court, outside the Court. Everything was just kind of an intranet. And that was because of security. So now we are allowed to access the internet from inside the building. But we do move slowly for security purposes. So, I don't know. I'm sure AI is going to come to the Court at some point, but I would expect for it to be a while.

Fred Ryan (50:52):

Have you wondered whether some of the people who are being questioned during Court cases have used AI to prepare for their questions? Anticipate what you asked?

Amy Coney Barrett (51:01):

Fred. I mentioned this to Fred a little bit earlier, so I understand. I have it on good authority that some lawyers who practice before us have prepared for argument by asking AI, feeding AI the case, and then asking AI: "Well, what questions might Justice Barrett ask in this case? What questions might the Chief Justice ask in this case?" And scarily, apparently sometimes the AI predictions pan out. And those questions actually do get asked.

Fred Ryan (51:34):

Well, just a final question to ask you. You're currently the youngest person on the Court, and we talk about AI and changes in technology, but this institution will certainly evolve during your years on the bench. Do you have any sense of how it will evolve? How would you like to see it evolve?

Amy Coney Barrett (51:54):

I hope it doesn't evolve too much, right? The Constitution, as we were saying before, is more than two centuries old. And it's been amended, and it's changed, but it hasn't radically changed. We're fundamentally, and for the original Constitution, still dealing with the same document, and the Court itself hasn't changed very much in the most fundamental ways. So technology will change the Court, technology may change some of the ways the Court does its business, but I hope that fundamentally the way that the Court operates and decides cases remains the same because I think we've got a good thing going.

Fred Ryan (52:36):

Terrific. Thank you. Thank you for putting together this book, and thank you for coming here to talk to us about it. And I hope when you have your next book, you'll come back, and you don't even have to wait until you have your next book. We'd love to have you back anytime, Justice Barrett. So thank you for joining us.

Amy Coney Barrett (52:55):

Thank you, Fred. And it was wonderful to be with you all.